Our story

This chapter

Where does Heynrich fit in?

Nasty, nasty!

Old goat, green leaf

More doubt again

One darn thing after another

Bibliography

Temper

Footnotes

|

|

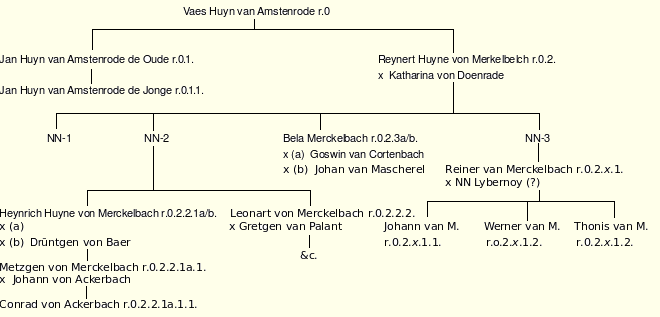

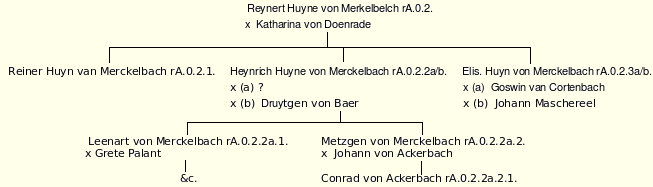

"We demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!" Last revision: April 13, 2008 The sparser the documentation, the rifer the speculation. Well after I obtained Rudolf Merkelbach's "De afstammelingen van Gregorius (Goris) Mer(c)kelbach," two different versions of the family's early genealogy have come my way. I shall refer to them as Table VIIIe and the Vanblaere version.* Table VIIIe is a part of what I at first assumed to be a reproduction of Max Dechamps's Der Ursprung des Geschlechtes Merckelbach, but it has since became obvious that it was a typewritten copy with (some) distinctly different charts of segments of the family tree. I am guessing at this time that these were drawn up by another historian, Eberhard Quadflieg. 3 Historian J.L.M.P.T. Merckelbach-Hovens gives us some sense of how widely ranging variations known to her are: "For example, some German sources claim that the Berger-Kölner nobel family Von Merckelbach genannt Allner sprouts from, or is even identical to, the branch Huyn von Merckelbach. However, the big differences alone between the coats of arms of these families tell us that this is most unlikely."* 4 Figures 1 and 2 show different versions at the very root of the Merckelbach family tree. These are presented as line diagrams to make the differences more immediately obvious than the vertical listings shown in Roots. Their captions tell the story, but it is the book by Max Deschamps that will not only assist us in shaping our judgment, but also lets us glimpse into the lives of some early Merckelbachs. 6  Figure 1. Root of the Merckelbach family tree as described by Rudolf G.F.M. Merkelbach in "De afstammelingen van Gregorius (Goris) Mer(c)kelbach. 350 jaar familiegeschiedenis" (1995). The book mentions that Vaes Huyn van Amstenrode had four sons, but we know the names and some details of only two of them. 7  Figure 2. This segment of the family tree follows Table VIIIe and corresponds with information given by Max Dechamps's "Der Ursprung des Geschlechtes Merckelbach." A generation of unknowns (NN-1, etc.) does not appear in this version. The Dechamps book states that Heynrich was a son of Reynart, not, as Fig. 1 shows, a grandson. 8 It has been found convenient to label some prominent branches of the family tree by the principal locals of their members. In the Trunk we identified a Straßburg branch, a Wittem/Mechelen branch, a Thimister/Frankenthal branch, a Grenzhausen branch, and a Soest/Hannover branch. Convenient, but not always fully consistent; after all, people often roam other pastures. The diverse interpretation shown in Figs 1 and 2 are not the only uncertainties encountered in the Merckelbach family tree. There are others that will come up later in the story. 9 Most troublesome at this time are uncertainties in the Grenzhausen branch, the branch to which our elusive Soldier of Orange appears to belong, the branch of especial interest not only to my family, but also to a distant niece, Margaretha Rosenstrauch-Märckelbach in California, and to the Merckelbachs of the well-known toy store in Amsterdam's Kalverstraat. Making the extensive genealogical jig-saw puzzle even more complex are snippets that pop up so now and then and in various places. What, for example, are we to make of the following fragment about a family that lived in Berg and Terblijt, near Maastricht? Reinier van Merckelbach ~1530 Among the children: A snippet like this may well be the missing link some researcher is looking for and so, even if it seems of little immediate use, it is well to keep it on tap for handy reference. But right now, we shall turn to the contents of documents and other information revealed in Dechamps's Der Ursprung des Geschlechtes Merckelbach. 10 From what little information we have about the twice-married Heynrich Huyne von Merkelbach (r.0.2.2.1a/b. or rA.0.2.2a/b.), he does not strike us as being an altogether easy man to get along with. But then again, he did have his problems. For starters a mild example: his tiff with a certain Tilman. 11 It is eternalized through a 1441 entry in the annals of the city of Köln. Heinrich Hune von Merckelbach, identified by Max Dechamps as Reinhard's son, begins a process against Tilman von Hotelen, a citizen of that city. In support of his case, he brings along two character witnesses: Johan Hoin zom Broich, "Here zu Velleruys ind zo Plenevaes" (Lord of Velleruys and Plenevaes) and a Johann von Withem. The first witness is emphatically identidied as "maege" (relative), specifically as a cousin. The second was, according to Fahnes Geschlechterbuch (Fahnes family register), a son of a Katharine von Hoenbroek. Heinrich did not win his case, to say the least. An entry dated May 25, 1442, rules that Heynrich van Merckelbek, Schulteiß for Vrechen, shall let Tilman zom Huetlyn off the hook because the complaint was not made in good time. and furthermore, he and his sons and daughters shall leave the city in peace. He shall, therefore, be sommoned with six guarantors to make a sworn declaration on May 28. 12 Heynrich, who claimed to have suffered deeply by his adversary's words, slanderous actions and writings, pleads to have his case taken up by the Palantine Court, but city council declares that Tilman can be held legally responsible only within the city's walls. Heynrich, being in the service of Count Werner von Palant as a Schultheiß*, requests his Lord to intervene. This led to an agreement to give Heynrich another day in court, this time in Köln's Minoriten monastery. On record as witnesses to Heynrich's character: After his first wife had died, Heynrich married at the advanced age of sixty the much younger Druytgen von Baer. The young couple took up residence in the bride's parents' home in Köln, but soon this led to difficulties with Druytgen's father, Peter vo Baer. Heynrich then moves in with his daughter Metzgen and son in law, Johann von Ackerbach, on the Buttergasse (Butter Lane, that is, if a translation is desired). Problem is, Druytgen refuses to come along with him. Heynrich threatens her and reproaches her for unseemly behavior. Attack being the best defense, Druytgen takes him to court and sues him for 600 "oberländischen rheinischen" guilders still owed to her by marriage contract. The records of the case, kept in Köln's archives, do not make for edifying reading. Heynrich does not mince words, "Du in leys dyr nyet genuegen myt eynre du hayss. Hude dich noe du wylt, ich wyll dyn allet dat affbernen, da du hayss." (You are not satified with what you have already. Watch yourself, you savage, I will burn down everything you have.) 14 Druytgen is equally plain spoken: It is also not right, to steal a dress from ones wife's chest to give it to a maiden. It is well known about Frechen what he did there. Heynrich had her bodily threatened and twice went after her in the streets shouting, "Ich wyll der vuyle hoeren yr naese affsnyden. Ich weuld ir arme en beyn intzwey slaen ind machen se dat sy nummer man ne gedoegen en suylde." (I shall cut the nose off that filthy whore. I shall break your arms and legs that you never will be able to please anybody." The court ruled that Druytgen, notwithstanding all that ever transpired, must fulfill her marital obligations. But she refuses and appeals to an official of the archbishopric Curia. 15 Three years went by when in 1450 Heynrich tries to solve the ongoing conflict with force. One day, upon entering the empty St. Alban church to pray, Druytgen unexpectedly runs into her husband and the Ackerbach couple as well as their son Conrad. They forcefully take her to the Buttergasse. Druytgen, hoever, does find a way out; she seeks help and the municipal authorities step in. Heynrich is arrested and incarcerated in the Bayenturm until, on November 24 of that year, an official in an appeals process pronounces his judgment. This time, a separation of table and bed is accepted and the city releases Heynrich to the land of Valkenburg after he signs a renewed sworn declaration. 17 On November 21, 1455, Heynrich is back in court for yet a third time, now before the Kurfürst, Dietrich von Köln, himself. The judgment turns out favorable to Heynrich. The parties' attorneys arrive at a compromise: Drytgen had lived separately from her husband for fourteen years and withheld from him rental income and goods. She had refused, against the sentiments of the Holy Church, to go back to him. Henceforth she shall turn over to him half of the goods and 800 rheinischen guilders. The losses amount to 1000 guilders of which 420 guilders are due immdediately. The burgomaster of Köln is appointed as arbiter in case the parties can't come to terms with the execution of this agreement. His judgment shall be final. And so, a long ungoing spat comes to an end. But by then, our hapless Schultheiß must have been about 75 years of age. 18 75 years old. This age is reckoned from the fact that Heynrich married young Druytgen at age 60 and that they lived apart for 14 years. That puts Heynrich's year of birth at ca. 1380. Given that Bela's husband received Passert's-Neiuwenhagen as a wedding present in 1395, that year 1380 accords well with the first time Bela von Merckelbach married. Marriages at a very young age were not uncommon in those days. The year that Bela's father married Katharine von Doenrade, given as 1371 (cf. Chapter 1, ¶ 7) fits ballpark figures. We have, as mentioned in the paragraph just cited, two estimated years of birth for her father: around 1330 and around 1350. Either way, he had been married to Katharina von Doenrade for about nine years when Heynrich was born. What I am driving at with these numbers is whether or not Heynrich's son Leonart is the grandson or great grandson of the first Merckelbach. Should we or should we not eliminate that generation marked as NN1, etc. from Figure 1? 19 When working on this Chapter, while doing revions revisions on March 29, 2008, what did I find on the Internet? Another story about the early Merckelbachs. Right here. Here follow, first, a copy of some relevant text in German, then a translation: "Die Geschichte der Familie Merckelbach geht zurück auf Reynart Huyne von Merckelbeich." So far, so good. But then: "Er war der Sohn des Ritters Jan Huyn des Älteren. Während der Brabanter Fehde kämpfte er 1371 zusammen mit seinem Vater und seinem Bruder Jan für den Herzog Wenzel I. von Luxemburg gegen den Herzog Wilhelm II von Jülich in der Schlacht von Baesweiler. Sie wurden gefangengenommen und mit dem Herzog in der Burg von Nideggen eingesperrt." In English: "He was the son of the knight Jan Huyn the Elder. During the feud with Brabant, he fought with his father and his brother Jan on the side of Duke Wenzel I of Luxembourg against Duke Wilhelm II of Jülich in the Battle of Baesweiler. They were captured and, along with the Duke imprisoned in the Burg von Nideggen." Well, well. That is quite different from what I understood before. Figure 3 reflects this Wikipedia account in which Jan van Amstenrade the Elder is suddenly metamorphosed from brother to father of our first Merckelbach. The account cites two sources. The first is Dechamps's book, the second is Leo Pierey, Herkunft der Merckelbach, Heerlen 2002. Fact is that the story actually does not jibe at all with what Max Dechamps told us, nor does it with what Rudolf Merckelbach wrote in his book, which is that Vaes Huyn was Reynart's father. I haven't seen the text by Pierey, but I am quite curious about what precisely it says. 20  Figure 3. Just Who is Who? An article in the Wikipedia describes the first Merckelbach's immediate family relationships as shown here (cf. ¶ above). One wonders what justifies this information and where it originally came from. 21 All is well that ends well: "Nach Zahlung eines Lösegeldes ließ man sie frei. 1374 wurde Reynart durch den Herzog mit der Belehnung von Haus Merckelbach belohnt. Seitdem nennt sich die Familie von Merckelbach. Reynart war verheiratet mit Katharina von Doenrade und hatte drei Kinder." Translation: "They were released upon payment of a ransom. Reynart is rewarded by the Duke [!] with the fief Haus Merckelbach. Afterwards, the family refers to itself as von Merckelbach. Reynart married Katharina von Doenrade and they had three children." Until I read this, I somehow believed that the Merkelbeek fief was transferred to Reynart by his father, Vaes Huyn van Amstenrode, but now it appears that Reynart was "belehnt" directly by Duke Wenzel. Had his father died? In the Battle of Baesweiler, perchance? 22 Max Dechamps wrote that Heynrich was Reinhard's son (¶ 13). But saying so does not necessarily make it so. The previously cited article by Ms Merckelbach-Hovens states that "some authors accept for good reasons that Reynart Huyne von Merckelbach is the father, resp. the grandfather of the previously named Heynrich and Leonard von Merckelbach." In footnote 18 of the same article, she writes, "The merit of Dechamps' manuscript is that it provides a very systematic of diverse Merckelbach genealogies and those of the related families [which is why I like using it extensively, vE]. A shortcoming is that it is rather short on naming sources." The Wikipedia chronicle agrees on this point with Dechamps: "His son Heynrich Huyn von Merckelbach became Schultheiß and Amtmann of the manor Frechen near Köln. His second marriage was with Druytgen von Baer, daughter of Peter von Baer in Köln. The marriage, however, was not a happy one and was dissolved in 1455 by the Kurfürst of Köln, the archbishop Dietrich, after a process that lasted for eight years." Heynrich's son Leenart von Merckelbach inherited his position in Frechen and, according to the Wikipedia article, owned, in 1463, the Hof "zo Dauwe" on the Huntzgasse in Köln. He was married to Grete Palant, daughter of the well-to-do Reinhart von Palant, a citizen of Köln." I believe that something is wrong here; I don't think that "zo Dauwe" was the name of the Hof; just a tiny matter of interpreting the meaning of quotation marks. But more about that in the next chapter. 23 Let's check the timeline a little further. In 1385, Reynert's cousin Jan van Amstenrode Jr. was a squire, see Ch. 1, ¶ 10. Assuming that a squire would have completed his preparation for knighthood by the time he is 20 years old, it follows that he was most likely born between 1365 and 1375. But the Battle of Baesweiler was fought in 1371; in other words, Jan cannot have been much older than ten years at the time. Even though he was probably not directly involved in the fighting, still, this young age makes his participation in the battle something hard to believe. But ten again, this suggests that Jan Jr. was not there at all, only the two brothers. Genealogy is just one darn guess after another! 24 Bibliography

J.L.M.P.T. Merckelbach-Hovens, "Het Wittemse patriciergeslcht Merckelbach." Limburgs Tijdschrift voor Genealogie, 32, June 2004, pp. 44-48. The author refers to a critical analysis of this issue in K. Nierau, "Zur Geschiechte des Belgischen Adels: Die Von Merckelbach genannt von Allner." Zeitschrift der Belgischen Geschichtverein, 83 (1967), pp. 1-52. For some snippets about Merckelbach gnt Allner found on the Internet click here. * fn2 Re. Merckelbach and Momboirs: 1 and 3. * fn3 The functions of a Schultheiß varied with locale and over time. A Schultheiß, acting in his Lord's name, may be head of a Schultamt, a local form of governance, in which he is assisted by aldermen, burgomasters and other officials. A Schultamt served to administer a town or a manor, maintain order, enforce the law, and handle any criminal prosecution. It was uually part of a larger structure, the Drosamt, headed by a Drost. The title points to one who Schuld heischt, a debt or tax collector. A dictionary translation is sheriff, but that is rather off the mark. For a fuller discussion, click here. * fn4 |

--

| top of page |

|

Page maintenance:

Page format:monh xx, 2015

Story edit:

To be checked for timeliness:

¶ none

Reminders:

¶ none

Linkcheck: not done

XHTML verify: not done

Backups: month. 25, 2011