|

|

Memories that never left her 1

Her name is Elisabeth. Spelled with an "s, she insists. Queen in her own right. Even with age taking its toll. 3 Getting out of bed, washing up and getting dressed, coming down the stairs, these all make a painful beginning of the day. Spinal stenosis, arthritis, maybe some nerve damage as well. Bent over, she pushes her rollator, smiles a greeting, straightens out a thing or two on the way to breakfast, and adjusts the temperature dials before sitting down. 4 Breakfast begins with turning on the TV and two capsules of a painkiller, but she often reminds herself, and me, how fortunate we are: "We have no cancer, and no dimentia." I don't say much because she can't understand people without first turning off a special gadget for listening to the TV that she wears around her neck. Most of her day is spent sitting in the same chair, 5 First thing after breakfast is turning on her iPad for correspondence and news, from the BBC mostly, and calling my attention to events she believes I am, or ought to be, interested in. Using the iPad can be confusing, especially with the pestering by hackers and the tiresome hard-to-grasp directions for updating her tablet. 6 She likes looking out the picture window, at the trees, at the birds landing on the feeders, at the squirrels squireling. She still is as active as she possibly can be, making her own coffee in the morning and doing other little things, doing some exercises, making desert for our evening meal; even works the laundromat and dryer. 8 She used to love reading, but that has become too tiresome. Other interests she has few after having had to give up running the household the way it should be run. Boring, right? Yes, but content nevertheless. Especially with the attention, companionship, and help she gets from our daughter. Then there are tea-time and "happy hour" and chatting with our son's family using FaceTime. They used to visit, but not now what with Covid-19 spreading. 9 She was quite reluctant leaving her nice home for an uncertain future in Canada. "You'll never make a good emigrant's wife," her father once said. How little we know one another, even our own children! She turned out to be tough as nails throughout many a hardship I exposed her to. Sometimes someone says, "We know so little about you" to which she responds, "You never asked." Then the conversation turns to other things, most of the time. 10 Am I boring you to tears? Please remember that, these stories are about me and, more importantly, my world. And some lessons we all might draw from them, and from what other people have experienced. 11 My wife, "mammy," has always been adept at social chit-chat, and always been a good story teller as well. On the phone once with Evelyn, our daughter-in-law, they talked about a TV program from England, about a family re-enacting the war years in London, and mammy talked a bit about her own years during the war. Then Evelyn said, "Mom, you should write this all down. The outcome: "Memories That Never Left M—WW-II Years," put on paper for our children, their children, and so on. Among them, stories about Jewish people who found shelter at her home. And a story about a harrowing trip late in 1944. I singled these out from many other memories of her youth. 12 * * *

"We got a frantic phone call from Katrien Bottema, who lived two houses away and had contact with an underground resistance group. She asked my parents to temporarily hide a little Jewish boy in our home. His parents had been transported by train to Germany, but the underground got this kid. Pietje was his name; only three years old." 13 That, I guess, would have been a year or two into the war, or later maybe. 14 "So, Pietje came in our family, a little shy, lost boy. I can't remember how long he stayed. Well do I remember that very soon I began scratching, scratching my head ... in the end with all my ten fingers scratching all over my scalp. Mam said, 'Child, what are you doing for heaven's sake ...'. Well, I guess you all get the picture, Pietje had lice and in no time we all got lice .... God almighty, mam got busy with vinigar and all kinds of stinking stuff, combing till the skin came off, and Pietje's hair was totally shaved off. Poor kid." 15 My quotes are slightly shortened for brevity. And her memories, written about seven decades after the events, are not in a neat, chronological order. But true nevertheless. 16 "After Pietje we got Loesje Berns, a nine-year-old girl. Her parents and four-year-younger brother had been transported to Germany." Enroute to an extermination camp most likely. "On the railroad station were people from the undeground trying to save cildren. Jewish parents would push them off to the side when no German seemed to be looking. Loesje came to us and later stayed with Katrien Bottema for a while." Because of the severe food shortage beginning in the Fall of 1944, "My mother cycled Loesje all the way up North, to the Province of Groningen, to a farm where there still was food. By that time we were starving." 17  Willie, Hans, Elisabeth and Elisabeth's mother. This photo was taken late in 1942. My future spouse was 15 then. 18 "This photo was taken after mam and I were at a church wedding. We had two Jewish children with us, Hans and Willie, who were then hiding at our home. Mom stayed on for the wedding reception while I took the children home right after the service. We felt safer that way, avoiding questions from people we knew. Both children and their parents made it till te end of the war and we kept contact with them for a while. Thinking about it, it was quite a stunt to take the children to a wedding, but we tried to give them as much of a normal life as possible." 19 Hans and Willie even attended school. They were aware of the danger they were in and knew to keep their mouth shut. Their parents were in hiding in a house to the back of where Elisabeth lived, on the other side of a high hedge. From notes by Elisabeth's mother, her children together with Hans and Willie sometimes sang children's songs while their mother, Mrs Meijer, listened behind the hedge. Hans and Willie were not allowed to say "dad" and "mom," but "uncle" and "aunt" instead. But one time, when the children were roller skating, a strap of one of Hans's skates broke. Mr. Meijer just happened to visit Elisabeth's parents and Hans said, "Darn it, dad, can you fix it?" Mr Meijer froze because at that very moment one of Elisabeth's much younger sisters, who were not supposed to know about the ruse, walked into the room. 20 "We also had an elderly Jewish man for a while. He somehow managed to give Adje, my youngest sister, a beautiful doll for her birthday. He used to be in the toy business before the war. ... I also remember a professor, a very nice gentleman. We didn't have him long, for safety reasons. Always on the move, secretly, with false papers, etc." 21 A year into the occupation, people from 15 years up were required to always carry an ID card. Jews, besides having the wear a yellow Star of David on their outer clothing, also had a "J" printed on their ID card. Those cards made a perfect instrument for the Nazis for rounding up Jews and men. 22 "By late 1943 men between 16 and 60 were picked up from the streets and transported in army trucks to work in German factories, or dig trenches, and so on. One hardly saw any men outside; they went into hiding and, of course, there were no more male teachers. My school came to a stop." 23 "We once got a 19-year-old Jewish girl, Anita. One day she had to go to another hiding place. I was asked to bring her to Baarn, about 15 km away. My sister Toos went with us, more or less as camouflage, making it look like an innocent outing, the three of us. Anita had false papers. We got instructions what or what not to say if something would happen." 24 The roof's configuration lent itself well for a trusted carpenter to make a hiding place. "Mam also hid there some food and blankets from being stolen by he Nazis. Later, much later, the carpenter was picked up and killed. We also learned that some hiding places were no longer safe anymore." 26 One day, a "good" police officer told Mrs Bottema that the neighborhood would be raided that night. "The professor did not want to bring our family in trouble and dad had to quickly take him somewhere else. Mam needed to stay home and I was asked to take a 19-year-old Jewish boy, who was hiding in a nearby house, to Bussum [a village not far away]. I took back streets to try to avoid Germans. Oh my God, Fons (not his real name) was shaking all the time. I delivered him to a safe place and then cycled back as fast as I could. It was dark and past curfew." 27 "I remember it like it was yesterday. During that night there was a loud banging on the front door and yelling! It was the 'Grüne Polizei.' Our house was surrounded by police soldiers. My father, in his pyjamas, opened the front door. We were all awake in bed, including the two Jewish children, Hans and Willie, who slept in the same room as my sisters. A soldier shone flash lights over our faces. An officer standing at my parents' bed side asked my father who we were. 26 "Now I must tell you, my father was very tall, slim, with big, brown eyes, and had a bearing of authority, someone whose mannerism commanded respect. He loved nature, music, books, his home, and hated parties and social prattle." 29 "My father got angry and told him off. 'It is scandalous waking up people and children in the middle of the night.' The officer drew back and apologized, and told my father that he did not like what he was doing either. Thank God, he was not from te S.S. and basically a good person." 30 "Later, my father happened to cycle by his old high-school, which was now occupied by German soldiers. They took his bike. Dad asked for a receipt so he could claim it back after the war. This was all sarcastic, of course. They took dad by the collar and kicked him in the backside. When dad got home he said that he finally got kicked out of school." 31 * * *

"Food was becoming scarce. We had food coupons, but in the end there was hardly anything available anyway, so they became useless. Train loads of butter, cheese and other staples, machinery, and coal for heating went to Germany. In the autumn of 1944, it got really bad. Food supplies were cut off. This marked the beginning of famine." 30 This was especially so in the urban western provinces. Hunger caused Elisabeth to suffer from fainting spells. Mrs Bottema's parents lived in Kommerzijl, a little village in farm country, in the province of Groningen. It was decided that Elisabeth's mam should take her there, along with her much younger sister Toos. Here is the story she told of the trip, somewhat shortened: 31  An antique map of The Netherlands on which the trip described below has been superimposed in red. (By 1932, a causeway enclosed the Zuiderzee, then renamed Ijsselmeer.) 32 "We went on bike to Amsterdam, along the highway which is about 20 km. We had no food with us, only some food coupons, a small suitcase with some underwear, socks, and, I think, a childrn's book for Toos; I can't remember for sure. Only mam's bicycle had rubber tires. One could not buy rubber tires anymore. The Germans took those too. Toos and I had instead wooden strips around the wheel rims to fill the space between their flanges. 33 "It was pouring rain, a bad start. Soon there was a loud racket from my front wheel. The wooden strip came loose. Mam ripped it off while I firmly held the bike. It wasn't easy. It kept on raining and we started again. Now I rode on an iron rim. It was hard. We went on slowly, soaking wet." 34 "Holland is a flat country, the wind sometimes fierce, and November can be harsh. So we went and went, Toos only ten years old. Hour after hour, without food, nothing to drink, weak, cold, wet, and hunger worse than ever. I don't know how we did it, but it could not go on much longer, also beause also Toos had lost a wooden strip. Meanwhile spokes began to break off from my front wheel, slowly, one by one. 35 "A farmer on an old tractor, with a small manure wagon behind it, saw us struggling. He stopped and asked where we were going. Mam replied, 'To the harbor in Amsterdam' and told him the reason for our trip. 'OK,' he said, 'I bring you as far as I can.' In those days, few were interested in money, but mam had some booklets of cigarette paper and those were gold in those days. He put the bikes on the tractor and we sat down on the manure, sliding and slipping. It was a stinking, exhausting trip, but neither Toos nor I complained. Mam's face was hard, it had to be. My yellow, ill-fitting, lousy raincoat was filthy by now, but in those times we just didn't care; not even teeagers. What was a teenager in those days anyway? 36 "Finally we arrived in Amsterdam. Mam gave this helpful man some more cigarette paper and he was happy with that. We thanked him and walked with our bikes to the harbor, to a freighter to take us across the IJselmeer to the province of Friesland (Frisia) whence we would cycle on to Groningen, the next province up North. 37 "The ship left at 7 pm and should arrive at a port in Friesland, I think it was Stavoren, at 7 am. Mam negotiated hard with the captain to get permission for coming aboard. She offered cigarette papers and a diamond ring, asked him to look at me, pale and frail. Toos somehow was better off. After a quick look, he took the ring and papers and told us to get aboard with our bikes. There was no more room in the cabin; we sat outside on the open deck, tired and depressed. Just sat there, close together. 38 "It was dark when we left, no lights on the ship, just the noise from the engine and waves lapping against the hull. Soon we heard Allied planes that were heading for Germany; hours on end. We saw search light moving across the sky and heard the shooting of anti-aircraft guns. Then, all of a sudden, a German ship came alongside. Soldiers came aboard, shuffling people around looking for food and men sixteen years and older. Screaming and yelling from mothers and wives when boys and men were yanked away and beaten as they were hauled off the freighter to be sent away as slave labor. 39 "We arrived in the morning, got on our horrible bikes and continued our journey. Mam was given an address in Friesland where we could stop along the way. A letter explained who we were. We got there after some hours, a big farm. A woman had one look at us, took our clothes, fed us, and put us in warm beds. I remember starting to cry, kept crying till I fell asleep. Mams and Toos cried too; it all had been too much. Next morning, our clothes dry, we got breakfast and milk. MILK! We hadn't had milk for months. Soon we had to leave and thanked those people. They were shaking their heads as we mounted our rickety bikes. It was a gray, windy day, but not raining. 40 "Afer a while, our energy faded and hunger returned. Mam told us that she would knock on a farm door to ask for something to eat. Well, that was the last straw for me. 'Mam,' I said, 'You cannot do that, that is begging, you can't do that!' I felt poor, totally miserable. Now, looking back, I would think differently, being a mother. But as a teenager it felt differently. Mam was, and always has been, a fighter. She told me to shut up and walked along a driveway to a farm house and rang the bell. I wished there were a hole in the ground that I could have disappeared into, I felt so embarrassed. 41 "A stout woman opened the door, looked at us, not sure what we were there for. She was hesitant. Mam told her about us and where we were going. She got us in a warm kitchen; people inside were staring at us, She gave Toos and me each a slice of buttered bread and a glass of milk. Mam got nothing, awful. After we finished, we went to a barn where there was a toilet with no door. I did not like that, with cows staring at us. 42 "Then we went on our way again, more slowly now with more spokes falling out of the wheels, which were not so round anymore. From a side road came a small tractor pulling a covered cart. On the tractor sat a young farmer, very good looking to my mind, and on the cart's cover an older man, his father we found out later. They looked at us and stopped, then asked mam some questions about what she was doing there. 43 "Mam told them our story and that we were going to a family in Kommerzijl. Luck was with us: they knew that family. They were going to a nearby village, Grijpskerk. They put our bikes on the covered cart. Mam seated herself next to the old man, Toos and I climbed on the tractor's big front fenders, and off we went, very slowly. Once in awhile we stopped for the men to relieve themselves. We came to a small village. Mam had some food coupons and asked if there was a baker nearby. We stopped in front of a tiny shop where mam could buy one loaf of bread. We wanted to share it with the men, but 'No, madam, we aren't that far yet.' Mam, Toos and I, each had a big chunk and wolfed it down. It was so good! 42 "Much later we found out that father and son were in the resistance. They had been up all night staking out lights in a field for an Allied plane to drop ammunition and weapons. When they saw us struggling, they thought for a moment, and took us with us as a camouflage. We stopped at Grijpskerk where the men to unloaded their cargo. We all went into the house where the people gave us a cup of ersatz tea to warm us up. After many thank-you's, we got on our bikes for the final 30-min. ride to Kommerzijl." 45 * * *

Mammy's mom. Even though brought up happy-go-lucky, it was she who made her family survive five years of food shortages and oppression. 46 "Many years later, when mams became invalid with Parkinson's, osteoporosis, and arthritis, I visited The Netherlands every so more often. She loved it when she could have me all by herself and having our many long talks. Frequently, of course, they would be about WW-II. And then I said, 'Mam, you did what you could under those difficult circumstances. 47 "Then, with her piercing blue eyes, she looked at me and said: I closed my wife's book of memories that never left her. Now again we all are facing a difficult time with Covid-19 making the future ever more unpredictable. A time sent to try us. People eager to help, people bent on profiteering and stealing, and most people somewhere in between on humanity's bell curve. 49 Yesterday, our daughter, Elisabeth Junior, went out for groceries. She could still buy them. We think about what may be next, but mammy and I have learned not to dwell on things too long. And, as has become tradition, we still enjoy our "happy hour." 50

|

--

| top of page |

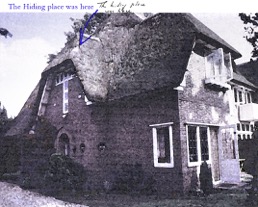

|