Our Story

"Greyed-out" titles are merely envisioned

Setting the stage

1. The first Märckelbach

2. Doing the genealogy

3. Bones of contention

4. The elusive "Soldier of Orange"

5. Are we alone?

Legends

6. The legend of Emma's rode

7. No rest for the wicked

Genealogy: methods

8. Form follows function

9. A pedigree chart (Van Eyken)

Parents of our soul

10. Ascendance

11. The prehistoric mind

12. It is written

13. Moving bodies and souls

14. Roots of Christianity

15. Orderliness is next to Godliness

16. Doing as the Romans do

17. Saint Gregory's truth

18. Blessed are the warlike

19. Charlemagne's legacy

20. Medieval feudalism

Deep roots

21. Nobiscum Deus

22. On to Anstelrade

23. Our heraldry

The first Mer(c)kelbachs

24. Duking it out

25. The Battle of Baesweiler

26. The hapless Heynrich

27. Serving the Von Palants

28. Those powerful "mankamers"

29. Serving the Counts Von Salm

30. Clay, iron, beer, and wood

Branches and twigs

31. Stories galore

32. Twigs for the picking

Etcetera

33. Reaching beyond the End

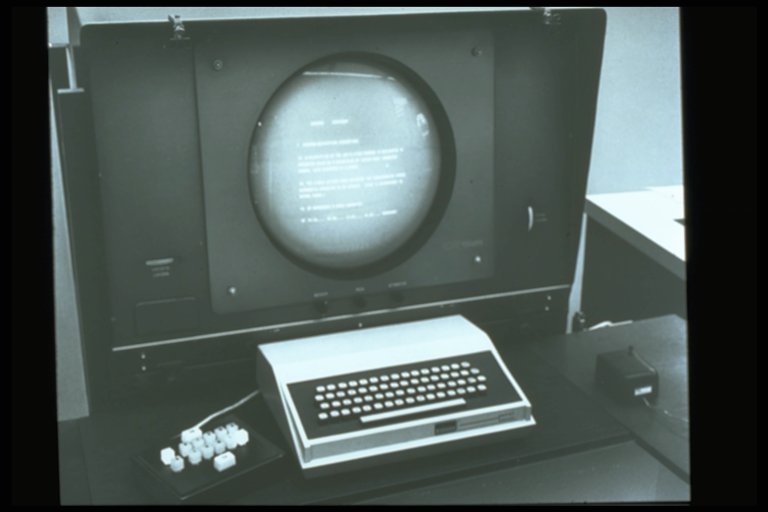

34. Of docs, digits, and DNA

35. Explorers of the past

Special thanks for valuable assistance by:

Peter Kreutzwald

Harald Merckelbach

Rudolf Merkelbach

Ger de Vries.

1A 0

And other most valuable help: Michelle Asjes, Peter Bohrer, Margaret ("Margie") Markelbach, Xenia Merkelbach and her immediate relatives. 1B 0

|

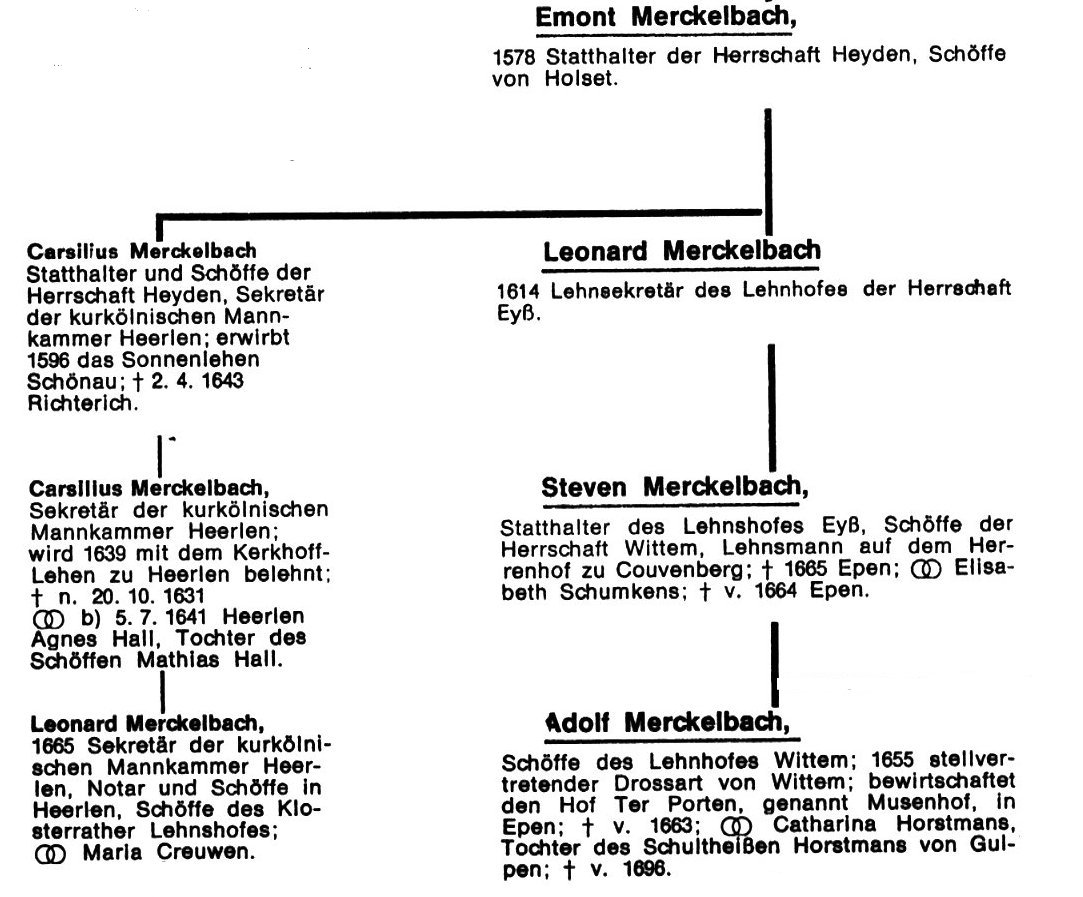

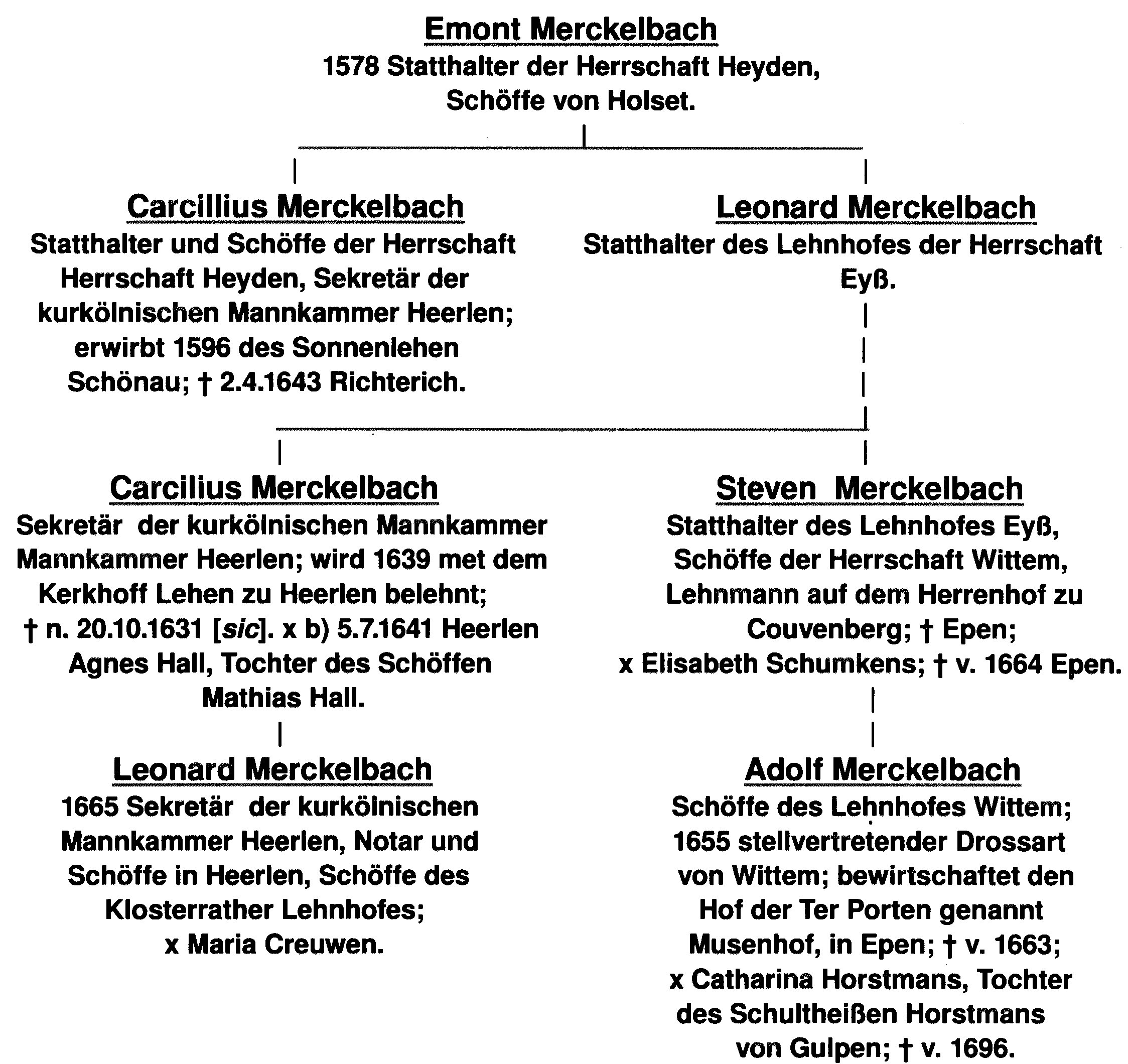

THIS IS ORIGINAL VERSION OF WHAT IS NOW CHAPTER 3. October 16, 2010 What a difference a word makes! Upon receiving a copy of the book, Nederland's Patriciaat.* I tried to fit the Merckelbach ancestry as published there into my existing versions of Trunk. But that did not quite work out. To see where the shoe wrings, go to a copy of that ancestry as found in Branches. The oldest ancestor listed there is a Carcyllys von Merckelbach, married to Cathryne NN. Then follows a long list of decendants beginning with Carcyllys's son Leonhard, who is the father of Steven. Turning to our Trunk, we find a corresponding list, but here it is Emont Merckelbach (t.1.3.1.2.) instead of Carcyllys von Merckelbach who is the father of Leonhard (t.1.3.1.2.2.). The Patriciaat tells us that Leonard has two sons: Steven, married to Elisabeth Schumkens, and C[arcillis]. It names a nephew of Steven: Leonardus, notary in Heerlen. Those pieces of information correspond to what we find in Trunk, but not to what we find in Dechamps, Der Ursprung des Geschlechtes Merckelbach. On this score the Dechamps manuscript and the Patriciaat do not merely disagree; they actually clash head-on. 3 The information in the Patriciaat is well researched, no question about that. The Dechamps document, too, carries a substantial degree of authority among those researching the Merckelbach ancestry. That document is, indirectly, the source for much of what is found in our Trunk which itself has basically been constructed from a database found on a site maintained by Peter Kreutzwald, whose work is gratefully acknowledged. A copy of the Dechamps manuscript now appears on this site; it can be found here. The script comes with a series of small tableaux, labelled VIII-f to VIII-l, of parts of the Merckelbach genealogy. Each tableau is followed by a discussion of relevant source material. The manuscript I received had stapled to it yet another tableau, VIII-e and does not only combine much of the content of the other tableaux, but adds some more Merckelbachs as well. Reproduced below is a part of that tableau. 4 Instead of Carcyllys, it shows Emont as the father of Leonard as does Dechamps' Tableau VIII-f. However, the text accompanying VIII-f does not really state that Emont is Leonard's father; it tell us hat Emont is vermütlich--presumably--Leonard's father, a presumption the tables morphed into fact. Furthermore, the Patriciaat speaks of two sons of Leonard (here named Leonhard): Steven and C[arcillis], and that Steven has a nephew named Leonardus, a notary in Heerlen. Tableau VIII-e shows a notary named Leonard, but not as Steven's nephew. However, that problem is resolutely "solved" by simply drawing a line as shown in the next diagram: 6 The added line accords with the family relationship described in the Patriciaat and is reflected in Kreutzwald's database and in our Trunk. Problem is, it does not really solve the issue for we find on page 9 of Dechamps: "A son of Carsilius, also named Carcillius, succeeeds him as secretary of the kurkölnische Mannkamer, and in the year 1673 already is his grandson Leonard notary and secretary of the Mannkamer in Heerlen." Reading this, we now face two dilemmas: Who do we choose as Steven's grandfather, Emont or Carcyllys? And do we accept as Steven's brother the Patriciaat's C[arcillis] as being the same person as the Carsilius of the diagram? 8 As for the second dilemma, suspecting a stiff dose of nepotism and influence peddling in the Mannkammers, I find it hard to accept this to be true. I am inclined to go with the two persons named Carsilius indeed being father and son and that, hence, it is the Patriciaat's C[arcillis] who is the father of Leonard the notary, not Carsilius jr. We can't be certain, of course, but this would be my choice if only these two options were available. However, one can think of yet another one. Might it be that the Patriciaat's Leonardus, the notary, is not the same as Dechamps' Leonard who was in 1665 secretary of the kurkönische Mannkammer? Might it even be that the latter was not a notary at all; that Dechamps melded the careers of two Leonards into one? That way the Patriciaat would be entirely correct and Dechamps almost correct. With the information on hand and applying the venerable Occam's Razor,* it is on this bet that I place my money. 9 Moving on now to that other conundrum: Steven's grandfather. Sticking with the Patriciaat, Carcyllys he darn well is; but where does he fit into the above diagrams? Might he be a son of Emont and thereby belongs to a generation that had been lost sight of? Or might he be a brother of Emont? Or does the truth lie somewhere else altogether? Pondering this question, I made a tabulation of dates relevant to the offspring of Emont's father: Johann von Merckelbach who in 1488 was a Rentmeister of Emont von Palant as shown in Tableau VIII-e. The purpose of this exercise was to see of we can get decent horizontal line-ups of birthdates in order to bring distinct generations into clear view. Although available birthdates are few and far between, by adding some additional dates from our Trunk's database (identified by ampersands) we hoped to make further half-decent guestimates of birthdates from dates of marriage and high points in careers. Here goes: 10

And wow! What pops up? 12 Look at the date Heynrich's son Reinhard got married: 1535. That is three years before the norm (i.e. some sort of average) for what is supposed to be his generation. Clearly, Heynrich and his immediate offspring belonged to an earlier generation. From what little information we have about Emont's career period (governor of the Herrschaft Heyden and so forth), it appears to fall in line with that of Thomas, Heinrich, Peter, and Gottfried. Page 9 of the Dechamps' manuscript strongly suggests that Emont and Reinhard are indeed siblings. What it all boils down to, for now, is that we have plenty of wiggle room for the patrician Carcyllys to fit in. Carcyllys may well be a son of Emont and the father of Leonard. This postulate demands, however, that there must exist also a generation between Reinhard and the elder Dietrich. Additionally, looking for simplest explanations, it then also becomes reasonable to posit that Carcyllys is the father of the elder Carcilius as well. 13 Time to turn our attention to Reinhard Merckelbach (t.1.3.1.3a.). And how fascinating! The database entry for Reinhard (Trunk entry t.1.3.1.3a.), presents us with a number of salient facts: 14 • Reinhard must have died after 1584 We discovered our missing generation! 16 Having established that after the sons of Heynrich von Merckelbach (t.1.3.1.) we ought to insert a generation, i.e. the younger Reynert in Straßburg and the Patriciaat's Carcyllys, we should also suspect that this Heinrich belongs to a generation older than that of the Reinhard who is married to Maria von Wirtzen (or Wierth), especially with their birthdates said to be 20 years apart--see above table. A 20-year gap in birthdates among siblings is, of course, not at all impossible, but it is cause for some suspicion. In our case we may be heartened by a comment on page 11 of the Dechamps manuscript, I'll translate: "In the year 1561, is 'Lord Thomas' assigned the position of priest of Bedbur by Countess Elisabeth, who, following the death of her husband, exercises regency over their four underage children. He keeps his old father Reinhard and his brothers Peter, Heinrich and Eymond with him in his manse. It's just what is meant by old. 17 One way of highlighting those places in our family tree where serious discrepancies occur is, as done in Trunk, by presenting distinct versions, and then section each version in such manner that sequences of names that are similar in both versions are identified as blocks: Block A, Block B, and so forth. It is then between those blocks that versions differ. I know, I know: I am ignoring that Block A is NOT the same in both versions, something I did not realize before writing this chapter. Moving on, though, we have taken things a step further in our workshop, which is the rubric named Lab Work. There, so as to even more clearly display where versions differ, I have shortened them by setting those identical blocks aside for separate viewing; see Versions 3 and 4 in the lab. Hyperlinks in those versions allow access to the blocks. 18 Having done this that bones of outragious contention jump out. To demonstrate, below are the relevant part of Versions 3 and 4: 199 Version 3 (from Leenart von Merckelbach and Grete Pallant up): 1. Leenart von Merckelbach × Grete Palant. rA.0.2.2a.1.

1. Leonard von Merckelbach ~1425. × Grete Palant. t.1. The first big, fat difference to hit us are the names of Leenart and Grete's sons. Adding further to the confusion are Versions 1 and 2 found in the lab. What to think? Next, consulting Dechamps, we find conflicting statements. The material pertaining to Tableau VIII-f tells us that the Johann, the 1486 Rentmeister of Neubach, was a son of Eymond, Rentmeister of Wittem. The next Tableau has us believe that the two were brothers. 22 Tableau VIII-e strikes a compromise of sorts: It shows Eymond as the father of one Johann and the brother of another, one who in 1471 appears on the financial records of Eyß. Tableau VIII-e mentions that around 1470 Eymond married an Adelheid von Mecheln. It streches credulity a bit that Adelheid is the mother of a son who under the age of 16 has a postion as Rentmeister. But that is not to say thet Eymond could have fathered Johann before he married, ca 1470, Adelheid von Mecheln. Certainly she was not the mother of the Jonann involved in financial transactions in 1451. 23 That contradiction between Tableaux VIII-f and VIII-g does open up an intriguing possibility, though; one worth keeping in mind. Could it be that Johann the brother of Emont is the father of Heynrich von Merckelbach (t.1.3.1.) and that Johann the son is the father of Reinhard von Merckelbach (t.1.3.2.), the one married to Maria von Wirtzen? That Heynrich and Reinhard are not brothers, that there indeed is a generational gap as their birthdates and the birthdates of their succeeding generations suggest? Could Max Dechamps' mistake of assigning to both Johanns an identical slice of careers have caused genealogists to believe that Heynrich and Reinhard were brothers instead of uncle and nephew? How beautifully would that sew up our case! Best, however, let's wait till if and when we can consult what others' reasonings and final judgements are. 24

In August 2010, from Prof. Dr. H.L.G.J. Merckelbach who sent me also a copy of Max Dechamps' manuscript, Der Ursprung des Geschlechtes Merckelbach as well other useful background material. return fn1 William of Occam is a 14th-century English logician, theologian, and Franciscan friar. Occam's Razor is a rule of thumb that considers the simplest of competing explanations most likely the one that is correct. This rule is the backbone of scientific progress. return fn2 This writer was for a number of years volunteer webmaster for what was then called the Bootstrap Institute. return fn3 |

--

| top of page |

|

Story edit: keep "as is"

Linkcheck: March 10, 2015

Webpages stor:

XHTML verify:

Workshop

Machine translations

Samples of translations done in September 2010 by iGoogle of this capter's original version:

and in November 2011:

I know these translations are bad and mostly so because I did not know about how machine translators work. But I did get some education from an article by Neil Coffey, here. With the rapid progress in machine learning, as evidenced by IBM.'s Watson's performance on the American quiz-show Jeopardy, one expects machine translations to improve greatly. H.v.E.